Economics

By Matthew Boesler2019年11月24日 21:00 JST

- Minneapolis chief backs monetary policy that can help low-paid

- He hired Obama economist to head new institute for inclusion

From Bernie Sanders to Warren Buffett, almost everyone says U.S. inequality is a problem. In 2019, big ideas about how to solve it have been in the air. One of the most unlikely solutions is emerging from a far-flung corner of the Federal Reserve.

Neel Kashkari, the outspoken dove at the Minneapolis Fed, says monetary policy can play the kind of redistributing role once thought to be the preserve of elected officials. While that likely remains a minority view among U.S. central bankers, Kashkari has helped lay the groundwork for a shift in Fed communication this year.

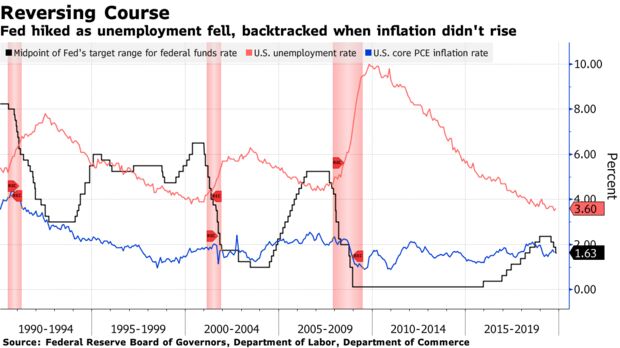

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues invoked trade tensions and a slowing global economy as they reversed course and cut rates three times in 2019. But they’ve also offered new explanations for their actions, focused on low-paid Americans.

Policy makers have acknowledged getting labor markets wrong in the recent past, and say they’ve learned from community outreach this year that many Americans haven’t felt the benefits of the economy’s long expansion.

All this rethinking has bolstered the case for keeping rates low at times when prices aren’t rising much — like the past quarter-century or so. And if the new ideas take hold, America’s next economic upswing may be overseen by a Fed that’s less inclined to raise rates in response.

Guiding Doctrine

As recently as 2018, both the policy and the rationale were different.

The Fed was tightening policy preemptively to foreclose on the risk that inflation would rise as unemployment fell. It also had plenty of experience of the damage that excessive inflation could do, not least to poorer Americans. Its guiding doctrine said that moving rates around can shift prices –- but not the structure of job markets, or the prevalence of inequality.

That was seen as a task for politicians who control government spending and taxes. When Kashkari, a year into his job, launched an in-house effort in 2017 to examine widening disparities in the economy, he was expecting to generate research that might inform lawmakers’ decisions, rather than the Fed’s.

“We had historically said: distributional outcomes, monetary policy has no role to play,” he said in an October interview. “That was kind of the standard view at the Fed, and I came in assuming that. I now think that’s wrong.”

Intensely Political

Kashkari’s project has taken an unexpected turn over the last two years, morphing into something more ambitious. It has the potential to transform an intensely political debate about inequality into a scientific endeavor that the Fed’s 21st-century technocrats could take up.

This year, he finally found someone to lead it: Abigail Wozniak, a Notre Dame economics professor, became the first head of the Minneapolis Fed’s Opportunity and Inclusive Growth Institute.

Back in 2015, when her eventual boss Kashkari was taking a career break after a failed bid to become Republican governor of California, Wozniak was a member of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers — where her work helped pave the way for the Fed’s paradigm shift.

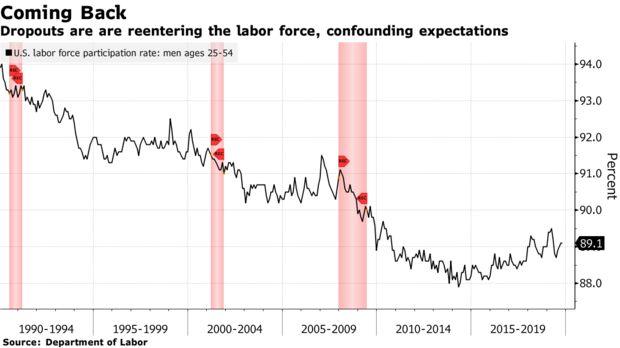

What ultimately changed Kashkari’s mind –- and surprised many Fed insiders — was the way the U.S. economy kept creating jobs, even as low jobless rates suggested that it should’ve been at or near full employment under old assumptions.

Instead, Americans who’d given up looking for work after the financial crisis -– and who weren’t therefore counted among the unemployed –- were pouring back into the job market.

While at Obama’s CEA, Wozniak was at the forefront of trying to figure out why so many men aged 25 to 54 had dropped out, according to Jason Furman, CEA chair at the time.

“We helped emphasize that supply explanations, like men not wanting to work, wasn’t a big source of the problem,” says Furman, who’s now at Harvard. The issue was weak demand –- which implied the trend could reverse, if policy makers let the economy heat up enough.

Really Resonating

Furman says he took Wozniak to a meeting with Obama –- unusual for someone of her rank -– and they clicked. “It became immediately clear that she knew more than any of the other economists,” he says. “What she was saying was really resonating with him, and moving him.”

Kashkari, who sits on the central bank’s rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee, wants to utilize her policy chops as well. He can designate a handful of advisers with clearance to attend FOMC meetings and says he hopes down the road to bring Wozniak into that inner circle.

In the meantime, Wozniak has the institute to build up. Eventually, she says, its work will feed through into monetary policy too.

One of its priorities has been to build a network of experts on income and wealth distribution, the same way the Fed brings in specialists in financial markets or growth.

“When we need to tap into the research network and say, what’s the state-of-the-art on this question, we can do that quickly because we’re kind of already there,” Wozniak says.

Ivory Tower

Mirroring the central bank’s wider efforts to engage with the public this year via “Fed Listens” events, Wozniak is determined to reach beyond the ivory tower too.

That was evident at Wozniak’s first big event as head of the Institute, an Oct. 3-4 conference on housing affordability. There were panels crammed with PhD economists -– but also presentations by local government officials and activists.

“We look on paper at the unemployment rate or other statistics and we try to come to a judgment about what full employment is,” says Mark Wright, the Minneapolis Fed’s research director. “That’s very different to what you hear when you’re on the ground talking to these people.”

Racial Segregation

The keynote address at the conference dinner was delivered by Lawrence Lanahan, a Baltimore-based reporter who wrote a book about housing segregation. After-dinner conversation quickly turned into a heart-to-heart on America’s legacy of racial discrimination.

For Wozniak, it was an example of what the institute hopes to achieve by bringing together diverse perspectives and challenging the way people think about pressing policy issues.

“We do want to try to foster that conversation,” Wozniak says. “I think that sometimes that means you take a risk, and you have someone who is outside the field present a strong view.”

While the Fed may be scanning a wider horizon, its immediate preoccupation is when or whether to resume cutting interest rates -– or pivot to raising them.

‘Material Reassessment’

Testifying in Congress on Nov. 13, Powell signaled that rates will likely stay on hold absent a “material reassessment” of the economic outlook.

A key question is whether the Fed’s new focus on inequality makes it more reluctant to raise rates if growth accelerates?

David Wilcox, a 30-year Fed veteran who ran the research department for its Board of Governors before retiring last year, thinks the answer is yes — with the caveat that the central bank’s actions must still be justified in terms of pursuing its congressional mandate for full employment and price stability.

“There’s more scholarship emerging that issues of engagement, issues of inclusion and issues of inequality are related to the overall functioning of the economy,” says Wilcox, who’s now at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“I think there’s the potential to change the decisions that are actually arrived at.”